Are you searching to regain happiness after your baby has died? You are not alone. Here’s a beautiful personal essay about how to stay strong after the loss of a baby.

NOTE: This is a guest blog written by the awesome-in-oh-so-many-ways Andrea Meyer!

When I walked into Aidan’s classroom, he was alone, pushing a matchbox car around the carpeted floor.

Clusters of kids were shaping play dough into snakes and sea monsters, dressing up as firemen and fairies, squealing about whatever games they play when they’re up in the loft-slash-secret hideout.

But my son was alone, pushing the same cars he was pushing when I left him that morning.

Usually when he spots me, his face brightens and he erupts—”Mommy!”—before launching himself into my arms. That day he glanced my way, pushed the corners of his mouth into a half-smile I read as sad and breathed a hushed, “Hi mommy.”

At the playground he seemed troubled, watching every move of another, younger boy, as if those moves would have a direct effect on his future happiness.

If the boy went down the slide, it would be momentarily unavailable to Aidan. If he darted suddenly forward, he might block Aidan’s path.

Aidan scurried off the play structure to instead run alone along the concrete bench that circles the playground.

Aidan scurried off the play structure to instead run alone along the concrete bench that circles the playground.

I told Harlan that Aidan seemed sad to me and he said, “That’s okay, he’s getting older.” Aidan turned four last month.

My sister says Aidan is the happiest kid she’s ever seen.

She also calls him a bandito.

Aidan has a smile that seems to stretch the width of his face and light up the room around him. It’s vibrant and beaming with mischievousness and mirth.

He loves nothing more than to run—fast and hard and far, with energy that doesn’t abate until we’ve screamed our throats achy and he stops, astonished that his fun has been unfairly and urgently brought to a halt.

But something has shifted in him and I worry that it’s my fault.

Behind a spirit that is generally full of joy lies a pensive little boy who can focus on reading a book or building a Lego tower for longer than most kids his age. He’s a child who from infancy has looked straight into your eyes with a stare that suggests he knows things about you he’s not sure he approves of.

He has an intensity, whether he’s running determined circles around the house or lining up cars in a perfectly straight queue, that can morph into an angry streak that flares unexpectedly like a skyrocket at the punishing voice or perceived criticism.

My little boy doesn’t like to be told he’s done something wrong. He’s across the room like a shot screaming, “You stop!” even at times hitting or biting or pinching my thigh, wanting to hurt me.

And that’s when I blame myself, because I too have a quick temper, I too study people and judge them, and, lately, I too have become sad and pensive, while I used to, at least most of the time, be happy and light.

When Aidan was a baby, people called him a Zen child and I felt that Harlan and I had imparted our shared mellow, sweet spirit to him.

But children are mirrors that reflect our less attractive qualities along with the good. The other night Aidan shouted at his dad, who’d asked him for the fourth time to put on his pajamas, “If you say that one more time, I don’t even know what I will do!” He was directly quoting me in an exasperated state.

When we left Southern California three years ago for Harlan’s job in Cambridge, I was distraught and eventually bitter about the move.

Since, I have struggled to find friends and work in an unfamiliar town where people tend to be slow to warm. I have felt socially awkward here, unable to read people’s reactions to me, worried that they don’t appreciate my booming voice and generally animated state.

One friend says, “They’re the kind of people who make me feel like Fran Drescher!”

I always kind of feel like Fran Drescher, or like my boobs are hanging out of my shirt. I’ve modified my behavior and felt myself become someone else, someone who isn’t always sure how to behave.

It doesn’t help that I lost a baby in my ninth month of pregnancy during our first year here, a trauma that cast a shadow over me, dimming the light I always felt defined me.

When I see Aidan playing alone, I perceive him as a lonely only child, where earlier I might have marveled at his ability to entertain himself. Our family of three sometimes strikes me as sad, even though there’s so much love and laughter between us.

I worry that my sadness and irritability are what define me now.

And I worry that they are the forces actively shaping my son.

Sometimes when I’m exasperated, Aidan throws his arms around me and says, “It’s okay, Mommy. It will all be okay,” as if he wants to take care of me.

It’s supposed to be the other way around.

But when I don’t know how to make myself feel better? When I have no idea how to fix my life?

I’ve tried writing about my loss and blogging about my struggle to find balance. I’ve tried cleanses and yoga and meditation. I’ve tried cardio binges and drinking with friends.

And I have to face the fact that I just don’t know how to make myself a happy person again.

Maybe that would be okay if it were only me.

Most people aren’t happy.

I was one of the lucky ones.

But I am terrified that I’m draining the joy from my son, that I’m turning him prematurely anxious, angry, steeped in thought.

That is something I cannot bear.

I need to get my happiness back so I can give it to my son.

Written and shared with love by Andrea Meyer.

For more about Andrea – and read more of her incredible writing – please click here now!

Think happier. Think calmer.

Think about subscribing for free weekly tools here.

No SPAM, ever! Read the Privacy Policy for more information.

One last step!

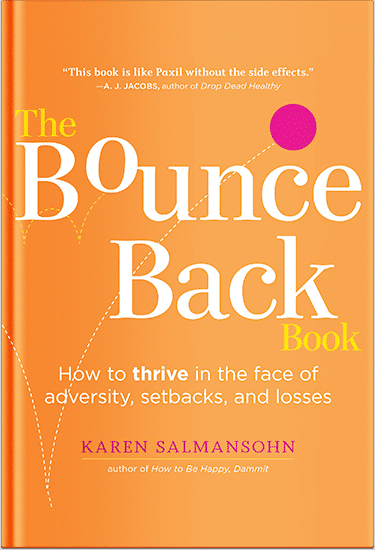

Please go to your inbox and click the confirmation link we just emailed you so you can start to get your free weekly NotSalmon Happiness Tools! Plus, you’ll immediately receive a chunklette of Karen’s bestselling Bounce Back Book!

Aidan scurried off the play structure to instead run alone along the concrete bench that circles the playground.

Aidan scurried off the play structure to instead run alone along the concrete bench that circles the playground.