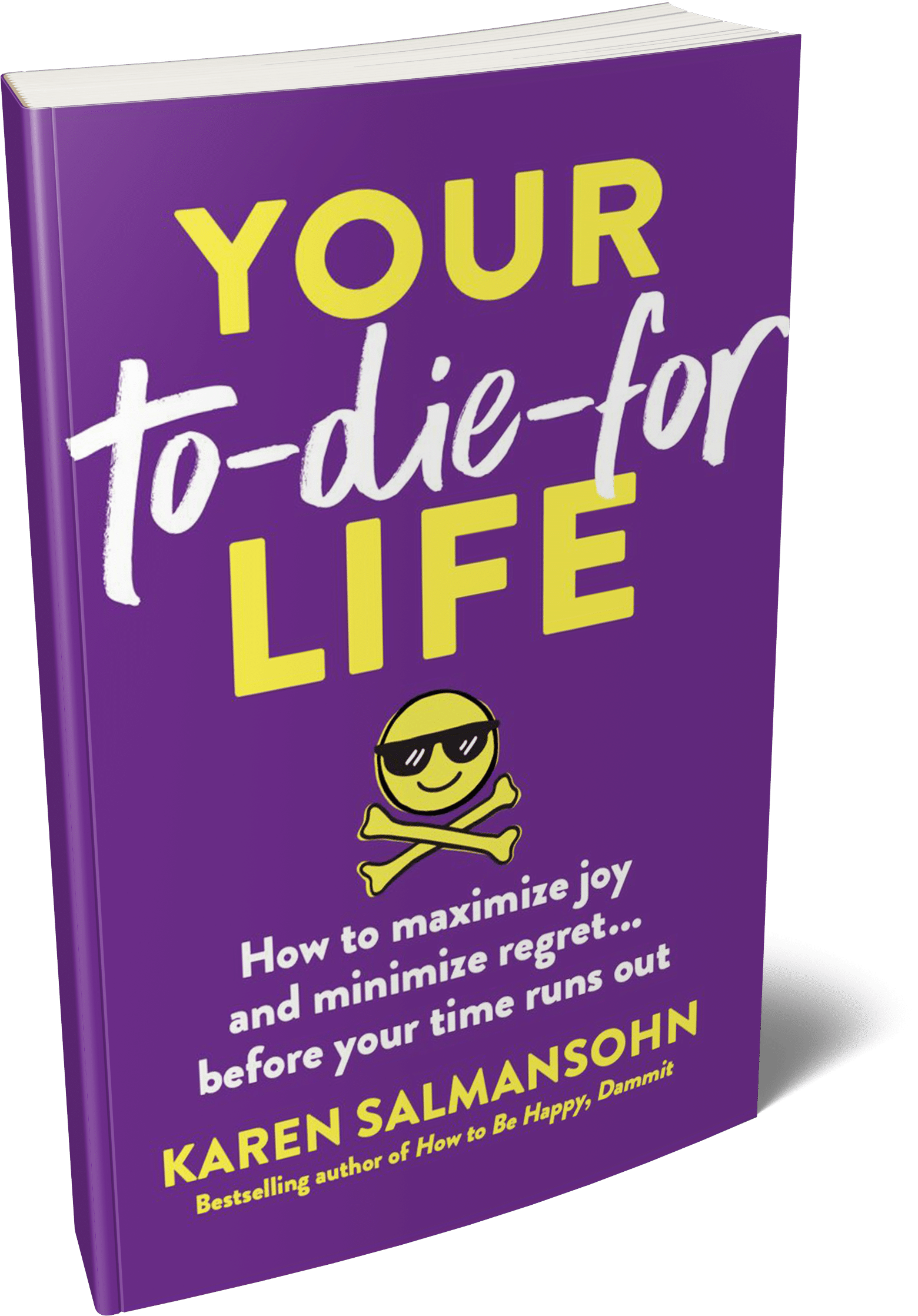

Get A Sneak Peek at my book “Your To-Die-For Life”!

Get a FREE sneak peek! Learn how to use Mortality Awareness as a wake up call to live more boldly.

A school closure gets talked about like a budget decision. And yes-budgets matter. But once the last bell rings, the building becomes something else: a community asset decision with real, visible consequences. If you’re tracking schools for sale, it’s worth remembering you’re not just evaluating a property-you’re stepping into a public narrative.

A school closure gets talked about like a budget decision. And yes-budgets matter. But once the last bell rings, the building becomes something else: a community asset decision with real, visible consequences. If you’re tracking schools for sale, it’s worth remembering you’re not just evaluating a property-you’re stepping into a public narrative.

Surplus school property can go one of two ways. It can slide into vacancy, vandalism, and neighborhood decline. Or it can be repositioned into something useful again-sometimes faster than people assume-if the process is structured and reality-based.

Responsible reuse is basically the discipline of holding three forces at once, even though they don’t naturally line up: Urgency: get the building back into use before it becomes blight. Equity / community benefit: preserve public value and avoid predictable harm. Feasibility: code, condition, partners, funding, and demand set hard boundaries.

Move too slowly and you get “years on the market” limbo. Move too fast and you get backlash, bad deals, or a beautiful plan that never opens. The projects that actually get delivered tend to have two things in common: transparent criteria and honest timelines.

Enrollment decline isn’t an abstract chart. It shows up as half-full campuses, duplicated overhead, and entire wings that cost money to heat, cool, and maintain whether they’re used or not.

National projections reinforce the direction of travel: public school enrollment has been projected to fall from 49.6 million in fall 2022 to 46.9 million by fall 2031, roughly a 5% drop. When staffing, transportation, and facility costs don’t shrink at the same rate, utilization becomes a financial pressure point. Facilities planning shifts from growth to rightsizing-whether communities like it or not.

Underutilization isn’t limited to a handful of big cities. One recent analysis found 68\% of sampled districts declined between SY 2019-20 and SY 2023-24, losing about 2 million students.

A lot of systems are operating smaller average school sizes even when formal closures lag behind the building math. That lag is expensive. It also creates a slow-burn problem: deferred decisions become deferred maintenance, and deferred maintenance becomes “this building is too far gone,” which is not where you want to arrive.

Closure patterns vary a lot. Policy choices, funding buffers (including hold-harmless provisions), and local politics can slow or speed action.

One reported snapshot cited 98 public school closures in 2023-24 across 15 states-enough to signal renewed closure activity, but uneven enough to keep planning uncertain district to district. That variability isn’t a debate point. It’s a delivery problem. Timing, constraints, and community expectations won’t be the same everywhere.

Responsible reuse works better when decision-makers are honest about what they’re optimizing. In practice, the strategies that hold up tend to balance four outcomes:

Here’s the tradeoff truth that keeps teams grounded: the option with the highest community benefit may take longer and require more subsidy, while the fastest disposition may leave public value on the table.

Responsible reuse isn’t about finding a perfect option. It’s about choosing a defensible one-and then actually delivering it.

Education-adjacent reuse often reduces friction because it matches the building’s original intent and many of its features.

Viability tends to improve when zoning is already compatible, the gym and cafeteria can be reused with minimal rework, and bus/parking patterns stay manageable. It’s also easier to explain to residents: the building still serves learning-just differently.

Civic uses can fit school layouts surprisingly well. Classrooms become program rooms. Libraries become public reading spaces. Admin areas become offices for service providers.

These projects often work through partnerships (city, county, nonprofits). But they live or die on operating funding, not just capital.

A renovated building without a funded program plan is a slow-motion failure, even if it looks great on opening day.

School-to-housing conversions can be transformative-senior housing, affordable housing, mixed-use redevelopment-but they usually demand deeper code work and envelope upgrades. The early feasibility flags are not subtle:

When these flags line up, adaptive reuse housing can create real public value. When they don’t, teams can lose years chasing an idea that never becomes financeable.

Sometimes the responsible choice is to sell, ground-lease, land bank for later, or deconstruct and create greenspace-especially when the building is unsafe, structurally compromised, or simply unfinanceable.

This pathway should be framed as fit-to-condition, not failure.

A community greenspace, stormwater feature, or future-ready site can preserve public value in a different form. It can also stop the bleeding of holding costs and deterioration.

Reuse outcomes are heavily shaped by condition and code compliance cost. A facility condition assessment should focus on the budget-and-timeline drivers that typically dominate:

The goal isn’t to “get a report.” The goal is to avoid beautiful concept plans that collapse the moment engineers and inspectors get involved.

Environmental issues can define scope and timeline more than design ever will. Asbestos, lead paint, PCBs, and other hazards are common in older school buildings. They affect both renovation and demolition strategies.

In some cases, contamination or complicated remediation pushes a site into brownfield-like territory, with specialized planning and funding pathways.

And remember the compliance reality: asbestos inspection and, when required, removal requirements commonly apply during demolition or renovation. Waiting to “deal with it later” usually means later is more expensive-and more public.

Closed schools sit at the intersection of memory and need. Meetings can get emotional fast. That’s normal.

What keeps emotion from turning into paralysis is structure: publish decision criteria, disclose constraints, share a real timeline, and collect feedback in a way that can actually be used.

Plain-language materials help more than glossy decks. “Myth vs fact” sheets are quietly powerful too, because misinformation fills the vacuum when buildings sit empty.

Responsible reuse should include an equity screen that’s short enough to use and specific enough to matter. Questions like:

This isn’t about adding paperwork. It’s about avoiding predictable harm-and building legitimacy for the outcome.

Delivery structure shapes speed, control, and risk. Common models include district retention with a lease to an operator, sale with covenants or deed restrictions, nonprofit conveyance, public-private partnerships, or city/county acquisition.

One point that doesn’t get said enough: the operating partner matters as much as the owner. A strong operator can make a modest building work. A weak operator can burn through a great building.

Feasible projects usually layer a capital stack: grants, tax credits where eligible, philanthropy, program revenue.

Practical rule: match the use to the funding, not the other way around.

A common failure mode is a beautiful plan with an unfunded operating model. Capital gets attention. Operating dollars keep doors open.

The first 90 days are less about vision and more about stabilization.

Priority tasks include securing the site, preventing deterioration, gathering core documents, and setting the public process calendar. Immediate actions often include:

Not glamorous. Not optional. It’s what prevents a manageable vacancy from turning into a damaged asset.

A strong solicitation brings forward fewer fantasy proposals and more financeable ones. Good RFPs communicate constraints, required evidence of capacity, and the evaluation rubric upfront.

Clear criteria also protects districts and municipalities from “backroom decision” accusations-which can derail even good projects.

Interim use is one of the best anti-blight tools available. Temporary activation can include pop-up services, arts programs, training cohorts, or limited storage with safeguards.

The key is structure: safety plans, insurance, controlled access, clear rules.

“Anything goes” is not activation. It’s a risk.

Responsible reuse decisions tend to succeed when they are criteria-led, diligence-forward, and tied to a timeline that gets the building back into use.

A school closure is never easy. But a structured responsible reuse process can convert uncertainty into momentum-and keep a community asset from becoming a long-term liability.

P.S. Before you zip off to your next Internet pit stop, check out these 2 game changers below - that could dramatically upscale your life.

1. Check Out My Book On Enjoying A Well-Lived Life: It’s called "Your To Die For Life: How to Maximize Joy and Minimize Regret Before Your Time Runs Out." Think of it as your life’s manual to cranking up the volume on joy, meaning, and connection. Learn more here.

2. Life Review Therapy - What if you could get a clear picture of where you are versus where you want to be, and find out exactly why you’re not there yet? That’s what Life Review Therapy is all about.. If you’re serious about transforming your life, let’s talk. Learn more HERE.

Think about subscribing for free weekly tools here.

No SPAM, ever! Read the Privacy Policy for more information.